I’m back from my summer hibernation. I’d be overjoyed if this break from work had left me (miraculously) rejuvenated and spiritually replenished.

It has not.

Instead as my rose tinted glasses shatter, I am rudely brought back to reality and reminded that:

- the pandemic is well, still here.

- Trump remains a bigoted white supremacist, whose role as a rotting, moronic, orange zombie has exhausted even the most steadfast of Shakespearean heroes.

In conclusion, I still remain, yours truly, a cantankerous, insufferable opinionated feminist, whose only intellectual pre-occupations of the past month have been:

- Is it presumptuous to title my skincare book the “Only scripture worthy skincare advice you’ll ever need?”

- Black Lives Matter

- Colourism

- Why was Vadim, the semi-cute, Russian mobster killed off in McMafia?

I should warn you that this blog (and its sequel) have nothing to do with skincare and are just focused on my observations about Black Lives Matter.

I’ll resume my normal routine of skincare blogs, but I have to get a few things off my chest first.

My view of the world is not the same as yours: my feminist perspective

My entry point into any discourse about African-American progress is through a feminist route, that is naturally shaped by my own life experience and research as a woman of colour.

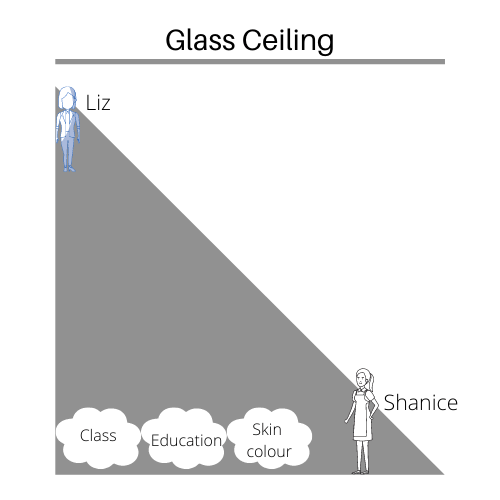

This is how I view the glass ceiling: its of different thickness and material depending on whom you are. Elizabeth or Liz and Shanice are my flagbearer Caucasian and African-American women occupying opposite ends of the opportunity spectrum. By opportunity, I mean the ability and means to shatter the glass ceiling.

Liz rowed crew at Yale: her mother is on the board of multiple charities, including the local hospice. Her father is a political lobbyist with Joe Biden on speed dial. As vice-president of a big name American bank, the glass ceiling for Liz is metaphorically speaking, close to non-existent and easily shattered.

Shanice grew up in Harlem and ticks all the boxes of foster care, teenage pregnancy and school dropout. Shanice is still in her 20s and despite her 2 jobs, finds the time to attend night class. She aspires to be a lawyer one day like Martin Luther King, but better.

For Shanice, the glass ceiling is very much real and in my mind is made of an indestructible layer of diamonds and palladium.

My key takeaway from this model are that neither Liz or Shanice are outside the realms of possibility. However, the wealth disparity, supporting infrastructure and importantly, skin colour, make the same country, America, heaven for Liz and hell for Shanice.

This manifests itself in numerous statistics: Shanice is more likely than Liz to die during childbirth, as is her child. While both Shanice and Liz are likely to be paid less than their male counterpart, the disparity for Shanice is larger. Finally, sufficient studies that Shanice is less likely than Liz to ever get married. Even in love, Shanice cannot escape her skin colour or the circumstances of her birth.

My view of the world is not the same as yours: the PR problem

I find the word “truth” to be subjective and truly unhelpful in any discussion. But it forms the foundation of any moral discourse, which is bizarre because my “truth” is shaped by my experience, intelligence, outlook and is not yours.

When I read James Baldwin’s essays from the 1950s, I cannot get my head around how little has changed for African-American men in nearly a century. It is heart wrenching to read that the despair of Baldwin’s generation of African-Americans that forges their way (e.g.) into crime, has not changed one iota. In fact, the three strikes law has increased the America’s infamous rate of incarceration, disproportionately affecting African-American men.

African-Americans also carry the weight of slavery in their blood and I will be honest is hard for me to relate to, and I am coloured and trying to empathise.

Therefore, I cannot imagine being a white American trying to get my head around the undeniable plight of African-Americans, especially when words such as “reparations” are frequently thrown around. As a white American, I can only infer that my forefathers and I are complicit in contributing to the all but in name, current indentured servitude of African Americans.

As I said, the truth is complicated.

My twopence is that the plight of African Americans suffers from a PR problem and until quite recently, simply not enough people cared enough to do something about it.

And yet if there is to be lasting change such as reform of the American criminal justice system, there must be extensive buy-in from white Americans. Period.

Addressing the PR problem

In my view, the confluence of many events, has re-energised the Black Lives Matter movement and has given a human face to the plight of African-Americans:

- the lockdown, which amongst other things, has forced us to acknowledge the finite nature of life and caused a degree of introspection that is violently absent from our everyday lives.

- Social media’s role in capturing and quickly disseminating:

- George Floyd’s brutal death

- A pre-meditated crime, where a white woman dials 911 to accost a black birdwatcher

- Higher rates of coronavirus deaths in African American communities, highlighting poverty, poor health, and lower levels of health insurance. The pandemic also shines a positive light on essential workers, road sweepers, train drivers etc, who have had to go to work every day, so that others can be safe in their Hampton homes.

Out of these the lockdown protests, have arguably been the most effective at winning the hearts and minds of an overwhelming number of Americans.

Experiencing first-hand police brutality or simply the cruel treatment of a Caucasian elderly man has struck the right note amongst Americans of all races and ages.

There is finally buy-in to the plight of African-Americans.

Obama’s described this as a turning point. It is.

I hope that Americans don’t lose the momentum this moment presents. That there is not only real policy change dealing with police brutality but also that Americans take the time out to question their past and importantly, how they can build a better tomorrow for future generations.

I am encouraged that African American writers have climbed to the top of bestseller lists.

People are educating themselves and that’s great.

However, becoming an erudite scholar on African Americans solves nothing. Americans need dialogue between themselves to learn firsthand what the horrors of being African-American are, to somehow acknowledge this, forgive as appropriate and, move forward, together as one nation.

In closing, my fears

I believe that America is at a crossroads. This is the first generation of Americans, who in a long time can make a difference to the future of their country. I fear they will squander this opportunity because of how polarized America is as a country.

They have to vote at the local and state levels but importantly not be shy about talking about how to address the problems of African-American communities.

For their part, African-Americans must acknowledge their responsibility to future generations of African-Americans. It is not enough to talk about just reparations and blame apportionment. They must get over this and push for serious policy change and much needed investment in black communities.

For example, how can we ensure that more African American children graduate school? How can we provide them with food, books, time, security – things that may not be provided at home – to ensure that they succeed?

Good luck America: this is your chance to redeem yourself in your own eyes.